|

Oh, What A Beautiful Death!

Cemeteries, Remembrance and Nationalism Idith Zertal

Where memory and national identity meet, there is a grave, there lies death. The killing

fields of national ethnic conflicts, the graves of the fallen, are the building blocks of which

modern nations are made, out of which the fabric of national sentiment grows. The

moment of death for one’s country, consecrated and rendered a moment of salvation,

along with the unending ritual return to that moment and to its living-dead victim, fuse

together the community of death, the national victim-community. In this community, the

living appropriate the dead, immortalize them, assign meaning to their deaths as they, the

living, see fit, and thereby create the “common city” (Jules Michelet), constituted out of

the dead and the living, in which the dead serve as the highest authority for the deeds of

the living.

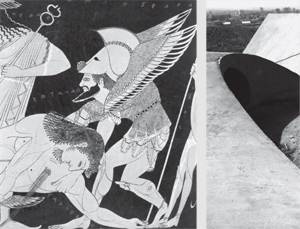

Ancient graves thus generate processes that create fresh graves. Old death is both the motive and the seal of approval for new death in the service of the nation, and death with death shall hold communion. Defeat in battles, those all too effective wholesale production lines of death in the service of the nation, are a vital component in the creation of national identity, and their stories are threaded through national sagas from end to end, becoming in the process tales of triumph and valor, held up for the instruction of the nation’s childrensoldiers- victims, who learn from these images and imagining to want to die (Idith Zertal, Israel’s Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood, Cambridge 2005, p.9). The concept of death for the sake of the homeland, which informs all future national deaths, is the Homeric death, Achilles’ “beautiful death” in the Iliad ( kalos thanatos). Achilles, the ultimate young man at the peak of his virility and glory, makes a choice to die in battle and in doing so represents in his own ruined, beautiful body the idea of the beautiful national death, as if the destroyed individual body were revitalizing the nation, endowing it with new, eternal life. This kind of self-conscious, chosen death becomes an indispensable ritual of initiation into a “life” of meaning, a life with no end, a perpetual existence, as opposed to the dull, wretched, meaningless existence of those who do not give themselves to the homeland. This beautiful death, death by choice on the battlefield, embodies the uniqueness and magnificence of the victim, at the moment of death and forever. The act that took the hero’s life, the hero’s death, endows his short life with retroactive meaning, as if he had been destined for this beautiful death, and his life is read and interpreted backwards as that of someone who while still alive had already been immersed in the glory of death. As Jean-François Lyotard wrote, “Die in order not to die,” was the meaning the Athenians gave to the concept of “beautiful death”. This was the exchange of the finite ( eschaton) for the infinite ( telos), the infinite life resulting from death by choice, the death which liberates from death. (Jean-François Lyotard, The Differend, Phrases in Dispute, Minneapolis, 1988, pp. 99-101) “Ro’i Rothberg, the lean blond youth, who left Tel Aviv to build a home at the gates of Gaza, to be a wall for us all,” said Moshe Dayan in his eulogy in April 1956 at the grave of the young man he had met only a few days before, “Ro’i – the light in his heart dazzled his eyes and he did not see the glint of the knife. The yearning for peace dulled his hearing and he did not hear the sound of lurking murder. The gates of Gaza weighed too heavily on him and undid him,” lamented Dayan, and by his very words he dispatched Ro’i Rothberg to the eternity of glory, bestowed upon beautiful heroes who know their death while still alive, and transformed him into one of the eternal living dead of Israeli mythology. War is the indispensable scene of the classical hero and an inherent part of nationalism. Death wrought by enemy fire, death on the national battlefield, is the prevalent variant of the classical hero’s model. The external manifestation of the internal criteria for excellence is glory, namely the texts which tell this tale of glory. Without a text of glory the hero is not a hero; he loses his unique heroic aura. The model hero always nurtures a value which exceeds his life, something which transcends him. Ro’i Rothberg was destined to choose to leave Tel Aviv and go to Gaza, in order to become a living dead hero. However, by losing his own life in battle, the hero attains, in modern times, a uniqueness that singles him out from the crowd, and positions him in blunt contrast with the masses without qualities of modernity and of modern nationalism.

Modern national armies, since the French Revolution, were built on volunteers and mass

enlistment, and therefore had to evolve systems of reward and compensation to those who

fell in battle or to their surviving families and friends. This took the form of the bestowal

of after-death glory and eternal youth, songs of praise and honour, eulogies by national figures.

World War I and its pointless mass slaughter of a whole generation of young

people from all nationalities transformed Europe into a realm of memory and marked the

commencement of official national commemoration ceremonies and rituals.

National cemeteries with their uniform appearance gathered unto them the nation’s

children, thus becoming the great social leveller, erasing differences in ethnic origin, class,

language, culture and rank. The poor man who was buried with national honour alongside

the bourgeois officer was delivered that way from a lifelong of destitution and anonymity

and was redeemed by death from a futureless life. Following World War I, commemoration

of the fallen and the erection of countless memorials and rituals of mourning, both public

and private, swept the entire society and transformed it into a community of grief.

An essential stage in the formation and shaping of a national community is its perception as trauma-community, a “victim-community,” and the creation of a pantheon to its dead martyrs, in whose images the nation’s sons and daughters see the reflection of their ideal selves. Through the constitution of a martyrology specific to that community, namely, the community becoming a remembering collective that recollects and recounts itself through the unifying memory of catastrophes, suffering, and victimization, binding its members together by instilling in them a sense of common mission and destiny, a shared sense of nationhood is created and the nation is crystallized. These ordeals can yield an embrac- ing sense of redemption and transcendence, when the shared moments of destruction are recounted and replicated by the victim-community through rituals of testimony and identifi- cation until those moments lose their historical substance, are enshrouded in sanctity, and become a model of heroic endeavour, a myth or rebirth (Zertal, Israel’s Holocaust, p.2). The modern state began to initiate official ways of commemoration and sublimation of its dead, first and foremost for its own sake, to supply the army’s need for conscripts, to ensure the reproduction of the thrill of the national sacrifice and to inflame the nation’s imagination and patriotic sense of belonging. Every battle was perceived as a fight for life, for the very existence of the homeland and its noble ideals. Thus the fallen soldiers in these battles could only be seen as sublime. It was a self-nurturing and self-perpetuating dynamic. Unnecessary, futile battles were elevated to the realm of and defined as existential battles, and those killed in them were sanctified. This move was essential in the justification of the fact that these redundant battles were waged in the first place and for the legitimization of their appalling price. On the other hand, the fallen for the nation, in whatever unnecessary and wasteful combat, sanctified the battle by giving their lives in it. The war experience underwent a process of sanctification in another way. The warriors, the fallen, most often total strangers to each other, became in the tales of glory brothers at arms, fighting companions with a unique sense of brotherhood and solidarity not to be compared to any other experience outside the battlefield. The more futile war was the more unnecessarily heroic sacrifices it demanded, and the more constitutive experiences it created for its soldiers. (George Mosse, The Fallen Soldiers; Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars, Oxford, 1990) The myth of national holy war and death for the sake of the homeland are notions which originated during World War I, precisely because of the flagrant futility of some of its biggest and notoriously meaningless battles and, due to the arbitrary and wanton way in which they were handled by the statesmen and generals of all feuding parties. This organized and comprehensive system of commemoration of the fallen, with its rituals and eulogies, and the sublimation and immortalization of the dead were destined not only to cover up the futility of it all, the deceitfulness of the entire war, but also for the taming of such unimaginable slaughter, the devastation of such unprecedented scale. Sublimation and at the same time domestication of death were in fact an attempt to blur its meaning, obscure its finality and irreversibility, dim the horror of loss and destruction and obliterate the experience of death altogether. The scope of the fighting in the1948 war, the constitutive war of Israel, conceived and universally understood as the existential, ultimate battle for the homeland, with its 5,700 fallen soldiers and civilians, (approximately one percent of the Jewish population) endowed it with the mythical dimensions of a world war. Its proximity to the Nazi systematic murder of six million Jews in World War II transformed the 1948 war into a Manichaean war, a total war between the forces of absolute good and justice and the forces of radical evil and malice. The discourse of the war and its dead took form, almost immediately, with the enshrinement of the experiences of the fighters themselves, and the ideological stance of statesmen, poets and publicists who, in many cases, were the parents of the young soldiers. It was a discourse of a homogeneous society, cohesive and committed, that used all its state resources, such as the printed press, poems, eulogies, memorial volumes, commemoration days and monuments, in order to immortalize the fallen children and give meaning to their sacrifice. The best and the brightest, the lost elites, the progeny, whether real or symbolic, of the leadership, continued to exist in the public sphere, to play a role, as major protagonists in the unfolding national tale. These models of discourse still prevail today, though somewhat transformed. For its domestication, concrete, material death in battlefield must undergo a process of diminishment, of silencing. As opposed to the amplification and empowerment of mythic life after death, factual and historical death, in all its horror, the devastation of the young body, the finality of life and the grief of those remaining, all go through a process of sterilization and mythologization in the national discourse. The nation glorifies victory, emphasizing its just way and the vindication of sacrifice. Personal death commands and enables the national life. “Blood will cover mothers’ feet/ But seven times will the nation arise/ If upon its own land it suffers defeat,” wrote Nathan Alterman in his poem “Now the Day of Battle has Finished and Waned.” The reality of Alterman’s mythical poem “The Silver Platter,” is of a twilight zone, a sort of no man’s land between life and death. The fallen in Alterman’s poem, says literature professor and essayist Dan Miron, continue to live in a certain way or a certain place and there exists within them a perpetual, intensive life whilst they have actually been dead. “Are they of the quick or of the dead?” is Alterman’s rhetorical question. The poem is depicting two young combatants, a man and a woman, whose death brings about a full-scale redemption, that is the yearned for State, a secular miracle. “Weary unto death” the young woman and man “fall in the shadows at the nation’s feet.” They are not actually dead, neither alive just “resting…by a hill near a flower.” The homeland awards them life and they “return” this life to the motherland (Dan Miron, Facing the Silent Brother: Notes on 1948 War Poetry, Jerusalem, 1992 p.188 [Hebrew]). Death is imprinted within a compensatory, superlative rhetoric and through it the fallen attain a dimension larger than life. They are bearers of a rare, unique potential which will never materialize, a future which will never come. There is rarely a resemblance between the portrayal of the fallen in the 1948 war, as well as in other wars, through their eulogies and commemoration albums, and the actual, humble youths who just before the war had been described by their parents’ generation as shallow, valueless and drab. Yet in a way the abstract portrayal of the fallen, the lack of reality makes them unattainable and indestructible. The non-real is non-obliteratable. That is how the fallen can be conveniently resurrected, on call, during national rituals and for national purposes. This technique enables to deal with the horrors of death and its demise, it appeases the feelings of guilt

for those who were responsible for sending these youths to their death. “Here they are the

glory of Mankind!/ Here they are pristine and brave! / Beneath a hail of arrows amidst the

blaze/ They march, with weapons in hand/ But in their hearts a precious vision flames/ Of

the prophets of justice and truth” (David Shimoni, “Hanukkah 1948”, reproduced in Miron, Facing

the Silent Brother, p.52).

“It was not for bloodshed that we aimed./ Our sons were trained for work and trades,” wrote Alterman, the national poet of the era of the establishment of the state of Israel, representing the hegemonic discourse of “no option,” the thesis of the totally innocent victim that release the nation from any responsibility for its choices and deeds, and their consequences, that is the death of its own children and the death of the enemy’s children. In the national discourse we are forever a nation pursuing peace, we do not hate, war has been forced upon us, we are the victims and will never forgive our enemies who force us to kill and be killed. The victims and the unending cycle of vengeful violence, of attack and counterattack, are always the responsibility of the other side. This is the national rhetoric that is produced and reproduced again and again according to circumstances, to forge the self-righteous nationals and make possible the unquestionable and self-explaining perpetuity of war. History, as it is written, interpreted and bequeathed, ideologized and politicized, conveniently begins at the moment the enemy attacks us, never with the sequence of events that led to the violent occurrence, nor with the historical background which has made the enemy an enemy and thrust him to act the way he does. Thus the prospect of a perpetual conflict and its dead is assured.

Translation: Aya Rupin. Poetry translated by Vivian Eden.

Professor Idith Zertal teaches Jewish contemporary history at the University of Basel.

Among her books: From Catastrophe to Power, Holocaust Survivors and the Emergence of Israel (Berkeley

1998); Israel’s Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood (Cambridge 2005); The Lords of the Land, The

Settlers and the State of Israel, 1967-2004 (Or Yehuda 2004, co-authored [Hebrew]);

Hannah Arendt: A Half-Century of Controversy (Tel Aviv 2004,contributed to and co-edited [Hebrew]).

|